23 Sep, 2011

After a chilly but friendly jaunt through the Black Hills and Rapid City, I headed off to the southeast in an ominous headwind toward the Badlands and Wounded Knee. For years, I’ve been looking forward to the opportunity to ride through the Badlands, and my proximity to Wounded Knee made for what seemed like an added bonus to that itinerary. Little did I know that my journey through the reservation would eclipse the wonder of the Badlands.

After a chilly but friendly jaunt through the Black Hills and Rapid City, I headed off to the southeast in an ominous headwind toward the Badlands and Wounded Knee. For years, I’ve been looking forward to the opportunity to ride through the Badlands, and my proximity to Wounded Knee made for what seemed like an added bonus to that itinerary. Little did I know that my journey through the reservation would eclipse the wonder of the Badlands.

History is clay that is never baked. We have the lump of matter—the basic events that transpire in particular places—but our minds are constantly shifting its form. In books and records, we are handed someone’s finished molding. To that image, we add our own finesse called experience—which compiles the opinions of others, the narratives passed down by those who are connected to events, some sense of the setting, and the like.

History is clay that is never baked. We have the lump of matter—the basic events that transpire in particular places—but our minds are constantly shifting its form. In books and records, we are handed someone’s finished molding. To that image, we add our own finesse called experience—which compiles the opinions of others, the narratives passed down by those who are connected to events, some sense of the setting, and the like.

Our experiences reshape history into our reflections—both literal and figurative. For example, when I think of Ephesus, I think of my experience of the place. I think of an impromptu run I went on with some Australians from Selcuk to the sea past the ruins we’d visited in the rain. I think of the cats and children I passed while strolling the streets of Selcuk. I replay the large, hostel-wide, family-style meal and playing songs for and with a chorus of travelers until the wee hours. I cannot read the book of Ephesians without that. I cannot study its history in a vacuum. There is no Ephesus without my experience of it.

At times, events in history reshape the landscape. Read this little factiod to learn about the US government's treatment of the Badlands in WWII.

As I shape my notions of history, there is very little that aids in creating a likeness than actually visiting a place. While biking through the Pine Creek Reservation, an unknown history was revived for me. In its awakening, I realized that its death was both real and interminable.

Throughout my childhood, I was told various tales about the people we called Native Americans. I absorbed the cultural imagery of Indians roaming the wilderness, fighting cowboys, and living separately. Apparently, these people had gone the way of the dodo and the dinosaur. In more formal settings, I was told the tale of the “noble savage” who had great knowledge of the land, the spirit world, and various cultures worthy of fine distinction. These people, too, had been killed off by the white man. The few remaining were like buffalo or emu that lived in isolated novelty areas that made a mockery of their once-grand civilizations. I heard about reservations and casinos and alcoholism, but the story most people told was of a people long past and the sad tale of their demise.

I raise this issue because I want to point out a sad truth: the marginalization of American Indians is so complete that we relegate a whole people to the past. In doing so, we ignore a present people and parts of our national and personal identities. Some who are older might point to the work of the American Indian Movement. Although events associated with AIM made headlines in the early ‘70’s, much of that history is entirely lost younger readers for whom American Indians are the epitome of cultural margins in the US.

This smelly puppy became my best friend outside the convenience store where I bought the breakfast burritos you'll read about later. So smelly, but very sweet! It was a very social spot. Got to meet tons of folks as they came in for weekend supplies on a breezy Saturday morning.

This older couple was great. I chatted with them for about a half an hour after devouring one of the advertised breakfast burritos. Very tasty. They told tales about growing up on Pine Ridge when there were no fences. Neighbors would return cows that had gone astray. The couple had spent years down in Arizona, but eventually made their way back to Pine Ridge. Here at Sharp's Corner, they were respected and liked by everyone who passed by. The burritos went fast.

As I made my way to the Pine Ridge reservation, I started to get reactions from white people that caught me off guard. Some quietly lamented the poverty on the reservation. Others were brutally racist. They told me not to cycle on the roads because everyone would be drunk. Some told me I might be beaten and robbed. Others told me to carry a gun to defend myself. Most of these comments seemed so racially charged that I dismissed them, but their harshness raised my guard a little.

In sharp contrast to these warnings, I met some incredibly kind people on the reservation. Almost everyone I passed engaged me in conversation that was compassionate and sincere. (This is a welcome change from the endless barrage of questions I get daily from folks who seem to think of me as some sort of public persona whose entire life is open to their commentary and judgment. C’est la vie a velo. I do my best to be patient.) While there is no shortage of poverty in Pine Ridge, there is an abundance of kindness to wayfaring strangers.

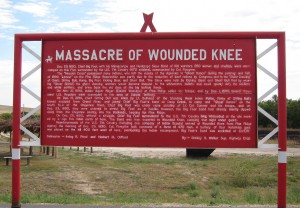

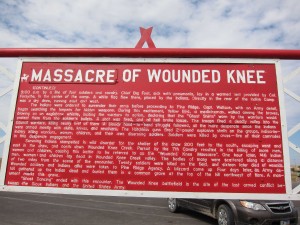

The following two pictures are the 2 sides of the sign posted at Wounded Knee. It tells a history which the folks in the area say is poorly shaped clay. They are working on a revision. Double click to open the picture in a separate window to read.

(back side of picture above) Conspicuously absent from the Wounded Knee area are the buildings and markers to honor the events of 1973. I found this to be a shame. As a whole, this is the most understated historical site of its significance in the United States.

After a somber period of reflection and prayer at Wounded Knee, I was about to hit the road when 3 folks at a tourist stand selling beaded jewelry called me over. I thought it was just for commerce, but it turns out they just wanted to chat. After 15 minutes or so, a car pulled up with an older relative of one of my new friends. They told me he had been there in ’73 and would be willing to chat with me. The older man stayed seated in the passenger seat of an old Chrysler sedan, and I kneeled in the dust beside the car. He told me about the tensions between full-bloods and half-bloods, about the destruction of the store and church that were the major buildings of the 1973 Wounded Knee incident, about his time in Vietnam, and about the way things are and were. While he spoke, his son brought over a stool for me to sit on and cold Cokes for both of us to drink. When it was time to hit the road, I thanked my friends with a gratitude hampered by an expected baksheesh for their kindness—which never came. They wished me well as they walked me to the dirt road that would be my shortcut east. The shared smiles were the only commodity we exchanged.

Not long after I left Wounded Knee on a great, hard-packed dirt road, a thunderstorm appeared on my tail. I came to a town where nothing was open, so I decided to ride on to the next town before the lightning came my way. As I cycled, it seemed unlikely I would make it to the next town, which was appropriately called Swett. I pedaled as hard as I could to the tune of approaching thunder and made it 8 miles to the town sign just as it started to rain and lightning spread over the fields of sunflowers along the road. Sadly, it appeared as though this town were closed too. The only visible building was an old gas station with a single, non-functional pump.

The lightning was so frequent that I grabbed both of these shots with a normal click of the shutter. I should have left the shutter open, but survival was more on my mind at the time.

As I sat watching the storm, I heard music in the distance. Upon investigation, I found the little Swett Saloon nestled behind the abandoned gas station. Inside, I quickly made friends. Turns out this was the “Indian bar.” Down the road 3 miles was the “white bar.” My newfound friends told me about their experience in this racially charged climate. They voiced frustration about the stereotypes they dealt with daily. They told me about life on the fringe of the reservation. But mostly, we just hung out and talked. Chewed the fat. That fat was tasty, and the table welcome.

Too bad this shot is blurry. I took it as I was leaving. In the foreground, you would see 4 friends, including the owner of the bar who microwaved a roadsnack for me.

This is Dwight and Sandy! We had a great chat for about an hour. They threatened to adopt me if I hung around any longer.

Outside the Swett Tavern. People liked to sit in their cars to drink, then come back in to hang out. Please reserve your judgments. Just like the rest of the country I've passed through, the bar is the center of rural American social life.

My schedule put me in Martin that night, so I said a reluctant good-bye to my Indian friends and hit the road as darkness washed over the South Dakota plains.